|

CIVIL UNREST IN THE BLACK COUNTRY 1750 - 1837

(Part Two: The Colliers' March of 1816)

by David Cox

The period between 1815 and 1822 was one of the

most difficult and troubled in British economic and social history

- George Barnsby refers to it in his classic book, The Working

Class Movement in the Black Country 1750-1867 as the 'Long Depression'.1

The wars with France had finally ended, and hundreds of thousands

of soldiers and sailors had returned to the home country, thereby

increasing the scarcity of food and employment.

In 1816, although over 16 million tons of coal were mined, over

one half of the total public revenue was immediately swallowed up

by payment of interest on the National Debt. Brian Murphy, in A

History of the British Economy 1740-1970, remarks that '1816

and 1817 were grim years for the iron-masters. More than one splendid

fortune turned to dust…' 2

This obviously had a concomitant effect on those employed

by the iron-masters. Once again, the scene was set for public unrest

at both the price of staple foods and the scarcity of employment.

However, the form of protest was gradually changing - George Barnsby

states that: From 1815, permanent and highly sophisticated forms

of organization appeared whose members and leaders were working

class people. The "mob" continued to play an important

part in political and economic struggles, but response to injustice

and repression was no longer entirely dependent on the vagaries

of mob reaction. 3

The reaction of the Bilston colliers and ironworkers seems partially

to substantiate this view; although a "mob" was still

involved in the immediate protests, the subsequent creation of

relief funds for the downtrodden does seem to indicate a more

sophisticated form of organization - however, these funds seem

to have been largely the response of the concerned middle class

rather than the working class.

The late eighteenth and early nineteenth century had been a time

of particular unrest and uncertainty with regard to food riots

- as Douglas Hay remarks:

| The

industrial region of South Staffordshire was particularly

likely to erupt in food riots…[There was] also a heavy

concentration of occupations (such as that of collier) which

had a reputation for collective direct action, in the form

of riot, sabotage or other direct intimidation of employers

and authorities, and the concentration of particular trades

in certain parishes helped generalise the phenomenon. 4 |

Increasingly intolerable distress faced by the colliers and ironworkers

of the Black Country finally caused their despair to spill over

in mid-1816, when groups of unemployed colliers decided to drag

waggons containing Black Country coal to London and Liverpool

in an effort to publicize their plight. Three waggons, each weighing

in excess of two tons, were dragged by hand from the outskirts

of Bilston to Oxford. From there, the three groups split, with

one heading to Maidenhead, another to St. Albans, and the third

to Beaconsfield.

The Times of Friday 5th July 1816 contained the following account

of the 'Colliers' March':

| The

colliers and labourers in the iron-works from Bilston, who

have advanced towards London, have, it is said, at length

been stopped by messengers from Government, advising them

to wait at some distance from town until the result of their

petitions shall be known. Government will doubtless give every

possible attention to their petition; but it is utterly impossible

that such wild projects should be attended with any beneficial

result, which might not be much better obtained by remaining

at home, and stating their grievances in writing to those

who have it in their power to afford them relief. What good

can possibly be obtained by losing many days labour, and incurring

the expense of a long and tedious journey, it would puzzle

the promoters of this ill-advised scheme to say. The waggon

which was to proceed by the route of Oxford, has already reached

the vicinity of Henley-upon-Thames; and another was reported

yesterday to have reached the neighbourhood of St. Albans.

In all that is stated about these unfortunate men, we do not

learn that they have any wish to encourage riot or disorder.

They foolishly entertain the opinion that the Prince Regent

can order them employment, and they pride themselves upon

being willing to work for an honest livelihood. Such is the

curiosity excited to see these extraordinary petitioners,

that many persons have actually left town in the expectation

of meeting them. |

This was the first of a series of reports that The Times carried

on the 'Colliers' March'. On Saturday 6th July 1816, it published

an 'eyewitness' account of the progress of the waggon that had

reached Maidenhead:

| Yesterday

morning (Thursday), Mr Birnie from Bow Street, accompanied

by 2 officers, arrived at the Sun inn here, and after consulting

with Sir William Hearn, and other Magistrates of this place,

swore in several extra constables; and as a matter of precaution,

ordered a party of military to be under arms. (see Figure

1) This done, they sent forward the officers from Bow Street

to meet the waggon that was approaching from Henley; it was

met on Maidenhead Thicket, […] and the crowd attending

it, on being informed that they would not be permitted to

proceed, instantly stopped, and conducted themselves with

the greatest propriety. The waggon, which was 2 ton, 6cwt

and 12lb, was drawn by 41 men; and a leader or overseer rode

on horseback and directed the whole. As soon as it was understood

by the magistrates that the party wished to act in the way

most agreeable to the lawful authorities, a negotiation was

entered into, and the coals were permitted to be brought in

here by four of the party and their leader, and were deposited

with Wm. Pyne esq., who will distribute them among the poor

of Maidenhead […] The men refused to sell the coals,

but gave them up as requested to Mr Pyne, and received a very

handsome present instead. Mr Birnie, Sir Wm. Hearn, Mr Pyne

etc went out and negotiated. The poor fellows were perfectly

satisfied, but refused to go until the magistrates signed

a paper that they had conducted themselves properly. At Henley,

the day before yesterday, they behaved so well that the Mayor

permitted them to go wherever they pleased in the town, and

they had upwards of £40 given to them at that place.

They left Bilston with three waggons in company, and parted

at Oxford. One waggon was to be at Beaconsfield last night,

and the other at St. Albans […]. |

These accounts of the good behaviour of the protesters helped

publicise their cause, and seemed to prick a few middle-class

consciences. Letters from middle-class gentlemen from Coseley

and Birmingham appeared in The Times, carrying accounts of the

terrible suffering being endured by the colliers and ironworkers:

When I have told these poor creatures

that the parish must find them food or labour, they have replied,

'Sir, they cannot do either', and some […] have said, 'We

would rather die, Sir, than be dependant on the parish'. […]

Some, I believe, have really died of starvation […]. An insufficiency

of wholesome nourishment […] produced diseases which terminated

in dissolution.

|

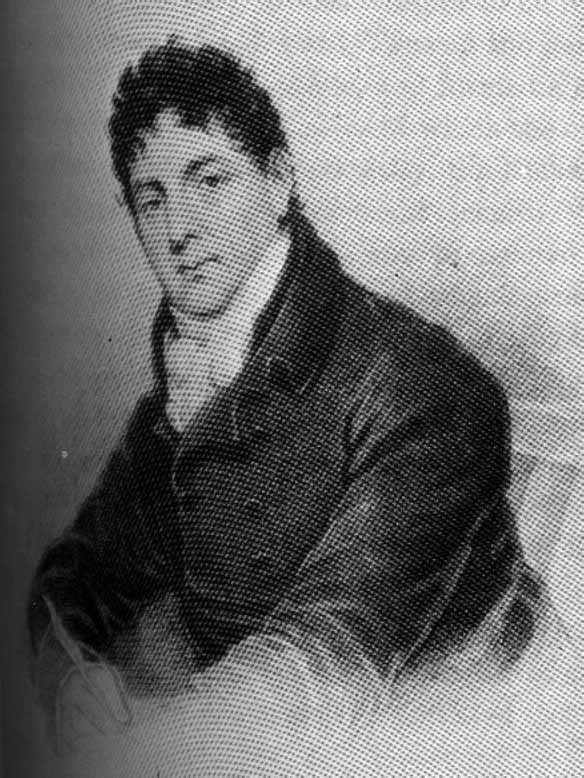

The picture on the right is of Sir Richard Birnie, Chief

Magistrate of Bow Street 1821-32. According to most accounts,

Birnie was a dedicated and reasonably humane magistrate

during his tenure at Bow Street.

Further letters of support and thanking those who had

donated to the relief of the poor of the area were published

on the 29th and 31st July.

|

|

|

Sir Richard Birnie, Chief Magistrate

of Bow Street 1821-32

|

On 5th August another letter was received:

The distress, Sir, is beyond everything

that has been described […]. I know, Sir, that other districts

are in distress; but our sorrows are of an earlier date, and consequently

of longer standing than those of any other county. Before the

peace was concluded our staple manufacture - our iron-works -

began to fail; and without help the pressure on our neighbourhood

is insupportable.

Richard Smith, of Tibbington House, near Birmingham, was the

author of this letter. He, along with Reverend B.H. Draper of

Coseley, helped co-ordinate the relief fund that had been created

to help the distressed. Despite funds being received from such

illustrious donors as Francis Freeling, Secretary General of the

Post Office, the distress unfortunately continued unabated throughout

the rest of the year. George Barnsby remarks that 'in

Christmas week the Wolverhampton soup kitchen was issuing 4,200

quarts of soup weekly'. 5

In the following year the Reverend Doctor Luke Booker, JP and

Vicar of Dudley, warned of seditious material

'…designing demagogues scattering their noxious notions over

the prurient minds of an unwary people'. 6

Although the popular agitation in the Black Country area did

diminish by the end of the decade, unrest in the area flared up

again spasmodically throughout the second quarter of the nineteenth

century. The most serious unrest took place in 1831, sparking

real fears of a nationwide revolution and these riots are covered

in depth in a three-part article by J. Robert Williams (The Blackcountryman

vol. 7 nos. 3 & 4, vol. 8, no. 1, 1974/5).

With the benefit of hindsight, this popular agitation can be

seen as the early stirrings of working class demands for a fairer

and more democratic society. That there was no popular widespread

revolution in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century

is perhaps somewhat surprising; despite the popular image of working

class unrest, the majority of the population remained remarkably

law-abiding and deferential to their unfortunate lot in society.

|

Notes

George Barnsby, The Working Class

Movement in the Black Country 1750 to 1867 (Wolverhampton:

Integrated Publishing Services, 1977), p. 4

2 Brian Murphy, A History of the British Economy 1740-1970

(London: Longman, 1973), p. 444

3 George Barnsby, The Working Class Movement in the Black

Country 1750 to 1867, p. 4

4 Douglas Hay, 'Manufacturers and the Criminal Law in the

Later Eighteenth Century: Crime and "Police" in

South Staffordshire', Past and Present Colloquium: Police

and Policing (1983)

5 George Barnsby, The Working Class Movement in the Black

Country 1750 to 1867, p. 4

6 ibid, p. 6

Acknowledgements

University of Birmingham Library

Dr John Archer, Edge Hill College, Ormskirk

|

email the web master Mick Pearson:

|