The

Thick Coal Seams of South Staffordshire

HD

Poole from The Blackcountryman Magazine Volume 1, Issue

3

The

term "thick coal seam" may convey an impression

that the seam of coal is solid and massive and 8-10 yards

in thickness. It is, in fact not one seam but a number

of separate and distinct seams or layers of coal numbering

from 10-15. The seams have been given names by the miners

who recognised distinctive characteristics in each seam.

It is difficult to give reasons for all the names.

| Benches |

This

seam was very often left unworked for, being a strong

coal, it prevented the unwelcome intrusion of the

soft clay-like measures from beneath |

| Dice |

Above benches, coal which easily

broke up into cubical pieces and was easy to remove |

| Slipper |

Seams of good quality coal |

| Sawyer |

| Patchells |

Seams about 12 inches thick |

| Foot |

| Stone |

frequently had a stone or dirt parting on top

of it. This parting varied in thickness and in the

Blackheath district was several feet in thickness,

necessitating working the lower section and then dropping

the stone and using it as the floor for the top section. |

| Veins |

Had special markings, not very good coal |

| Fine |

coal of better quality |

| Brazils |

hard and inferiour in quality. It would break

up into large cubical pieces or blocks, the author

saw a substantial wall built with this material. |

| Heath |

Usually the best qulaity of coal.

Evident to the earlier miners who worked considerable

areas of the top section and the Slipper and Sawyer

of the lower section, leaving the middle section to

posterity. |

| Floors |

| White |

| Spires |

| Rooves |

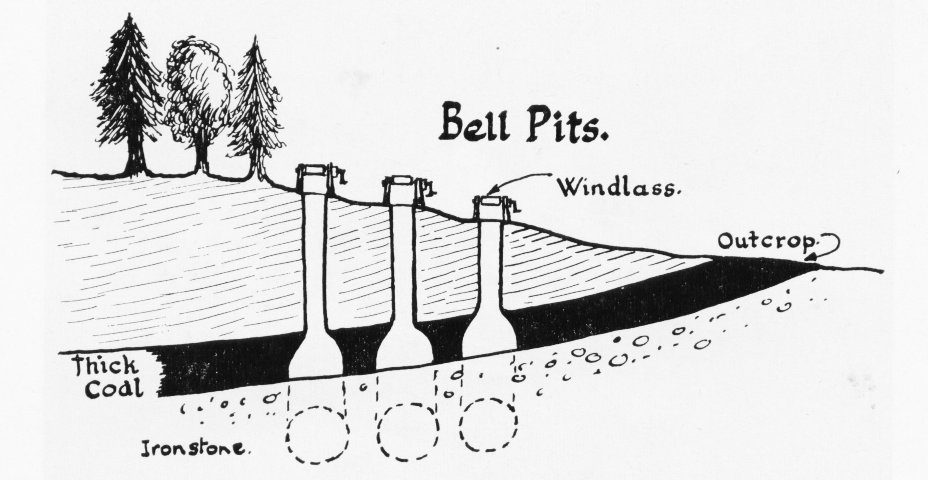

The first attempts at working the thick

coal to replace the use of timber for fuel were along

the lines of outcrop onto the surface. It was simply a

question of removing the soil to expose coal. It may be

coal had already been used as fuel because it could be

found on sea beaches where outcrops of seams occur in

cliffs. Waves were the cause of breaking up of the coal

and together with adjacent rock shaped into pebbles of

various sizes. This was known as "sea coal".

Although there were vast quantities of this in the course

of time miners were forced to follow the seam down, and

in order to reduce the amount of spoil to expose the coal,

were forced to begin sinking small shafts. On reaching

coal the shaft was continued but at a gradually enlarging

diameter until reaching the bottom of the seam. These

were known as "bell pits", and the reason can

be seen from the illustration below.

When bell pits had had there day they were

replaced by the sinking of shafts to greater depths and

the introduction of systematic methods of working the

top and bottom of the seam. The miner now became a skilled

craftsman who took great pride in his work and, as rules

and regulations were non-existent, his time was his own

concern. It is most probable his wife worked the hand

windlass to wind the coal to the surface.

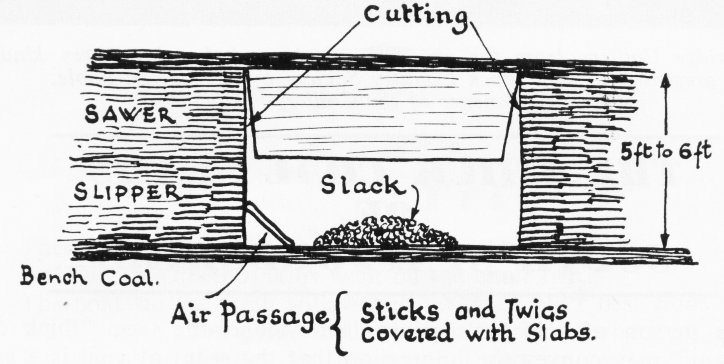

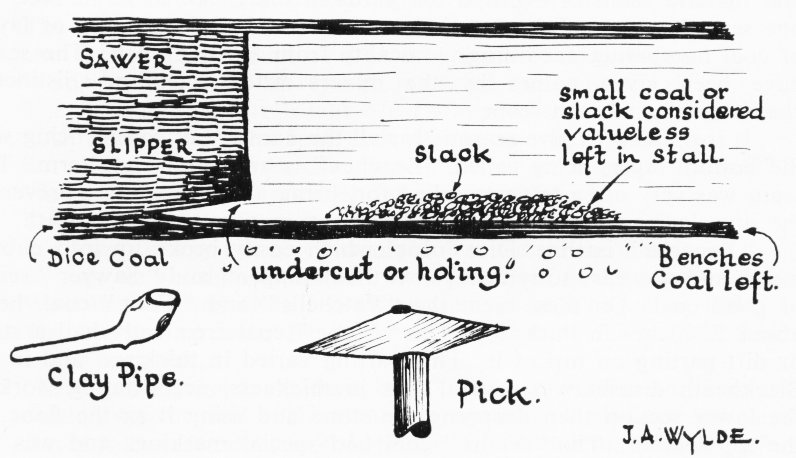

The skill and neatness of the miner - probably

from about the 14th century - were researched from first

hand study by the original author of the article. He was

able as a young student to inspect the stalls or working

places, as these were approached by workings from an active

coalmine. The coal being of a strong nature and the height

and width of the stall being small, the working places

were found exactly as left many years before. At this

time any coal was acceptable and the slack or small coal

had a ready market for steam raising. On entering an ancient

stall, one was impressed by the care and precision of

the miner. Vertical and smooth sides; neat undercutting

in the coal to prepare for extraction; an occasional small

recess in the side of the stall to hold his tobacco pipe

in a safe place, also his 3-handled drinking cup of which

examples can be seen in museums in the midlands. A miner's

pick was also found and the writer was impressed by the

heavy weight of this tool.

On one occasion a small shaft was found

and bones were exposed. The first thought was perhaps

that these belonged to a miner, but on further investigation

they were found to be of a deer and the small skeleton

of an off-spring. The position of this shaft was carefully

marked on the mining plan and it was found that an old

turnpike road was immediately over it. Just one more incident

in a lifelong fascination with coal!

|

The author

of this article - HD Poole - was General Manager

of Baggeridge Colliery from 1926 to 1937. The illustrations

used were taken from the article mentioned at the

top of the page. Mr Poole was 90 years old in 1968,

I would like to hear from anyone who could put me

in contact with his family, as I am sure they will

have many memories that they may wish to share.

Mick Pearson

|

Email the web master Mick Pearson:

.

|