Master Craftsman or just the Master?

(A history of Major Nichols and his Bicycles)

By Alvin Smith

Foreword

Major Nichols died in August 2005. This account of his life and work has greatly benefited from, and indeed perhaps has only been possible through the enthusiasm of a number of Major Nichols's old customers, family and friends. Major was still very much alive when this history was first started but as he suffered from poor eyesight at the grand old age of ninety plus years he would have been unable to read any part of this history. He did however know that it was being written. Major was indeed at that time barely able to recognise even old friends and the main author never met him, it being considered that a new face asking detailed questions would make him clam up as part of his self protection. However, when it was explained to him, he was pleased that it was being written although he responded with a typical Major outburst of "Why's he bloody well doing that, then?"

Honour Guard of Major Nichols cycles on parade in honour of the man.

The picture I have drawn of the man and his bicycles is mine and I take full responsibility for it but has been agreed by his old friends as about as true and fair as far as they remember, and together we, the writer and his closer associates, are pleased to be able to dedicate this account of Major Nichols and his bikes to the memory of both Major and Wynn, always known as Winnie, his adored wife, with whom he had shared the happiest days of his working life in both of his two shops.

Major Nichols and his eponymous bicycle, the Major Nichols, were well known in the West Midlands region and indeed in wider circles in the 1960's, '70's and '80's. The sporting lightweight frames were the choice of local, and not so local, cycle cognoscenti, whether it was for pure racing on track or road, or for touring. Major Nichols was still alive at the time of researching this story in 2005, but since 1995 his business, always a one man affair, had, like the man himself, retired from the limelight. The story of Major Nichols and his bicycles had already become shrouded by myth and part myth, partly fostered by people conjuring with his given name and in part due to his fierce-some reputation for not only knowing what you needed even if you didn't, but his no-holds- barred manner of telling you so. This account attempts to bring an awareness of this highly talented man and his wonderful bicycle construction skills to both local people and to other cyclists who might not otherwise have heard of him and his work, or who might see his bicycles in the streets and wonder about the story behind them.

The name Major was Major Nichols's actual given name. Major is a traditional Black Country Christian name, and is not an assumed rank. However, one story told by Alan Richards, who ran Tower Cycles and who was one of Major's oldest friends, is that Major's name had been chosen on sentimental grounds by his father, who had served in the Indian Army. The story went that this bias towards the Army shown by his father was the reason that Major chose to enter the Navy during World War Two. This is perhaps an apocryphal tale, though it does somehow ring true, whatever else you thought of him, Major was recognized by his many admirers as an uncontrollable force. Indeed, to many of his fascinated and often over-awed customers he was Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde personified. In his shop he could be part your best chum, part irascible genius. He just loved to display his knowledge and lay down the law of bicycle design to his customers, and if one mouse squeaked, well he knew how to handle that!

Major Nichols cycle courtesy of author

Hermione Walton, Major's cousin on his mother's side and who grew up with Major, remembers how as a child during the First World War, this characteristic was developing. His strict grandmother who looked after the two grandchildren at this time always called him 'The Varmint' for the problems he caused.

The loveable but commanding character that he could portray, he enjoyed playing throughout his life. He could be cantankerous, even, to use an American expression, sheer ornery at times, although, in the shop he was often welcoming and chatty. In conversation he could be domineering as he warmed to an enthusiasm over some point, but was often kind and generous to his customers when active in business. Many children remember him with fondness due to his rapport with them, whilst their parents could at the same time find him 'strong meat to take'.

Major was born in West Bromwich in the old family home at 5 Reform Street. It is still possible to walk the older streets around this part of West Bromwich close to the still wonderfully English Dartmouth Park with is great flower borders and get a flavour of the area that Major always loved and thought of as home and where he had met and grown up with Winnie Walker whose family, with six or seven other children lived just round the corner in Walter Street.

Major certainly came from a colourful family background. He had been born in Reform Street, on 17 November 1914, to his father's second wife, Maud, nee Hawkins who came originally from Great Arthur Street, Smethwick. His father's first marriage had produced two sons, Francis and Edward, who was known in the family as Ted or sometimes Nank. Major's niece on Wynn's side (Pat Slater) has said that Nank was looked up to as an athletic type by Major. Apart from Hermione Walton, nee Hawkins, none of that generation have survived to tell us about Major's childhood and early upbringing so the little we do know is based upon stories by Hermione and her daughter Marilyn and then from Major himself and related at various times to his friends in the bike shop.

Major Nichols father, Mr Nichols senior, had become a well-known local character. After his Army service, he had been a keen cyclist, winning numerous races and being semi-professional in that he took part in round-the-town races. Doubtless in these races on-street betting on the winner provided some further income over and above the prize money. Riding these events could be a very profitable occupation, netting good riders up to several thousand pounds in a year. Major told his old friend Barry Southall that at one time both his parents were in a stage trick cycle act. Barry remembers that Major also told him how exciting his home life could be as his mother let out rooms for B&B to the many colourful theatrical players who visited the area. Major also told David Clement, who came to work with Major briefly in the early 1960's that he had once been bounced on Col Cody's (Buffalo Bill's) knees. Checking this aspect has revealed that Col Cody died in 1917, and last visited the West Midlands area in 1904 so it is impossible for this to have happened to Major, though just possible that this memory was family lore passed down to Major from one of his older half-brothers or from his parents recounting the episode to him. To add to the colour and excitement it appears that Major's uncle, presumably his mother's brother was said at one time to have been employed by Al Capone in Chicago. Unfortunately his activities in the United States go unrecorded; perhaps because, as he was a big burly figure, no one dared to ask!

Major was said to be musical as a child and learnt to play the violin, which some say he continued to enjoy in later life, though if so members of the family do not remember it ever being brought out for them. Leaving school, Major trained in electrical installation, starting work with a company involved in heavy duty industrial work. For some time he used this knowledge when helping out on a voluntary basis at the local Palais de Dance operating the theatrical electrics. Apparently there could be up to six performances a day at times and Major remembers that as he had had to ride the eleven miles from home to the venue several times a day, he was physically exhausted at the end of a full day! He was professionally involved in the 1930's with a large contract to rewire the Birmid factory in West Bromwich. This large factory was at the time a local landmark and the firm was a very important employer, being a key alloy foundry for the motor trade and in wartime for the aircraft industry. Before and after the war Major enjoyed motorcycle touring. There were photographs on the wall of the later shop showing 3 or 4 motorcycles owned by Major in the 1930's and 40's and Major enjoyed recalling tours of the Cotswolds in the 1940's on his Rudge and other motor bikes. Then, like so many others he fell for the magic of the motor car as he was if nothing a sucker for any new technology.

| Visit theClassic Light Weights website for more information on classic lightweight machines built in the UK and Italy. The site includes a section on Major Nichols |

By 1939 Major had joined the Navy in which he was a Gyroscopic Compass Technician and served all over the world, leaving the Navy as Petty Officer. He recalls that in the case of one Royal Navy ship, for whose gyro compass setting he was responsible, the bosun told him that the ship had successfully depth charged (using the then new 'Squid' depth charge) the German U-boat from which their code book and encoder was captured by the Royal Navy. This allowed the German naval Enigma code to be broken, which was a significant advance for the Allies. Furthermore, the Captain of the U-boat had said that his capture demonstrated outstanding navigational skill by the RN ship, for which, of course, the gyro compass was an essential component. He added that, try as they might, the U-boat could not outrun the Royal Navy vessel. Naturally Major took personal plaudits for this piece of work and was fond of telling the tale. After seeing action in several war theatres, Major's last posting was to Sierra Leone where he was trainer in a Navy school for gun control directors. Here conditions were dire and the food deplorable, so that Major returned to this country as a shadow of his peacetime self and weighing less than 6 stone. At that time he had nothing good to say for the Navy or his experiences during the War and was always reticent about the details of this period. He had however, acquired a deep and abiding knowledge of 'below the decks' expletives and collected a rich vein of colourful invective, which continued to surprise a number of his shop's visitors when he had a bad day. He did always however have a soft spot for a fellow Services man for whom the door was ever open for a chinwag.

|

| Two more fine examples of Major

Nichol's machines (courtesy of the author) |

On return from the war Major met or at least renewed his friendship with Winnie Williams, his future wife. They were soon married and initially lived with Major's parents in 5 Reform Street. Later were able to move to a rented council flat in Denbigh Drive just off Black Lake Street, Hilltop. Then, perhaps when Maud, Major's mother, died, Winnie and Major returned to Reform Street.

Winnie became a real part of the business operation and perhaps because they could not have children they became very close as a team. Mrs Marilyn Smith, to whom Major and Winnie were 'Uncle and Aunt', remembers with fondness the happy days when Major and Winnie would join them, perhaps at Northwood Halt station near Bewdley, now the preserved West Midlands steam line, for summer picnics, jaunts on the train to the pub at Arley, or less occasionally at the seaside at Barry Island.

Recalling her childhood Marilyn remembers how Major would make a fuss of her and her young brother. She recalls how Major made her brother his first bicycle - a fairy bike - and how proud her brother was of it, that he sneaked the bike up to his room that night so he could go to sleep next to it.

Marilyn

also remembers that Major even as an adult could on occasion be

mischievous. Once he accompanied Winnie and her young charges,

Marilyn and two of her other girl relations on a blackberry-picking

expedition along the rail embankment not far from Northwood Halt.

Major suddenly shouted "Train Coming!" and Winnie, in

her panic, rushed everyone down the embankment - which at that

point was full of nettles. Marilyn continues - "Needless

to say we were in agony with the stings, and No, there was no

train at all!"

Marilyn

also remembers that Major even as an adult could on occasion be

mischievous. Once he accompanied Winnie and her young charges,

Marilyn and two of her other girl relations on a blackberry-picking

expedition along the rail embankment not far from Northwood Halt.

Major suddenly shouted "Train Coming!" and Winnie, in

her panic, rushed everyone down the embankment - which at that

point was full of nettles. Marilyn continues - "Needless

to say we were in agony with the stings, and No, there was no

train at all!"

Marilyn remembers when her family were all on holiday at Bewdley, how Major and Winnie would happily walk to the farm to collect fresh milk, though Winnie showed a townie's uncertainness of approaching the farm animals. Also how Major fell about laughing when one day he ran in to tell Winnie that the clothes she had hung over the fence to dry were being eaten by the farm pigs. And Marilyn still enjoys thinking about the ensuing chaos in the family. Above all, however she remembers the good times they all enjoyed together when her Aunt Winnie Uncle Major came round on Sundays, and how her Uncle would always 'lay down the law' and try to make sure there was no cheating at cards - and woe betide the person who tried to play a false hand even if inadvertently.

|

| Major Nichols pictured in 1969 |

Winnie was really a great help and support to Major, being the only person who could bring him back to earth (and work) once he had started talking to (or at) a customer, often interrupting him with "That's enough, Major". She also ran the retail counter of the shop so allowing Major to get on with frame building and doubtless saved him a lot of time, and self confessedly kept Major "on the straight and narrow". Roger Allen, who as a young cyclist in the early 1970's was a customer of the shop and who got to know both of them very well, recalls that if your wants were more technical than, say a puncture repair set, Winnie would give her bell three rings to fetch Major from his workshop.

In 1971 came an upheaval that perhaps defined Major's life - and certainly he felt that it did. Major had been told that he would have to move out of the family home because of a planned realignment of existing roads to make way for the new roads leading to West Bromwich's devastated town centre. This change, which ripped the centre out of the old town was, as so many residents saw it, wholly unjustified carnage by the 1960's town planners. Major had dearly hoped at one time to be able to celebrate 100 years of cycling trading from these same premises. He was intensely proud that the firm was known all over the world (Major's world appeared to end at New Zealand). In Major's view West Bromwich and its people together with his bicycle were, as far as Major was concerned, Second to None.

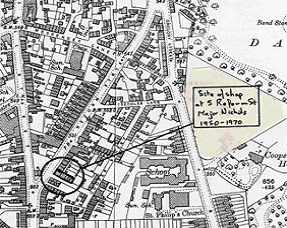

The new Sandwell authorities were not unkind but were unbending. They were adamant, though they sought as far as they could to find the Nichols an alternative site for the shop and home. In the end there were no suitable buildings in West Bromwich and Major and Winnie had to move to new premises in 48 Durban Road, Smethwick, in early 1971. The location of the Smethwick shop is shown below on an early map.

Winnie

Nichols, who had always suffered from asthma, gradually became

more and more affected whilst in Smethwick. It appears that although

she had suffered from this debilitating disease for many years,

she may have hidden the fact that she was getting worse from Major.

Many of their old friends also did not realize just how bad she

had been getting. As a remedy she started smoking herbal mixtures

obtained from the local herbalist's - this was when these shops

selling traditional herbal remedies were common in English town

and markets, well before the now ubiquitous Chinese herbalist

finally replaced them. Winnie smoked the herbal 'tobacco' in a

pipe and many were the smirks from young cyclists who found her

smoking her pipe semi clandestinely between customers. The smell

of the herbal mixture became part of the legends of the shop for

many young supporters. After not taking much notice of her condition

Winnie died, fairly young, in the late 1980's after a short but

debilitating final illness. David Clement who visited Major at

this time and took him to see Winnie when she was in hospital

says that her death really upset Major. Major felt, rightly or

wrongly, that the hospital had not done enough for her, and some

of his friends have said that the bereavement soured Major's outlook

on life thereafter.

Winnie

Nichols, who had always suffered from asthma, gradually became

more and more affected whilst in Smethwick. It appears that although

she had suffered from this debilitating disease for many years,

she may have hidden the fact that she was getting worse from Major.

Many of their old friends also did not realize just how bad she

had been getting. As a remedy she started smoking herbal mixtures

obtained from the local herbalist's - this was when these shops

selling traditional herbal remedies were common in English town

and markets, well before the now ubiquitous Chinese herbalist

finally replaced them. Winnie smoked the herbal 'tobacco' in a

pipe and many were the smirks from young cyclists who found her

smoking her pipe semi clandestinely between customers. The smell

of the herbal mixture became part of the legends of the shop for

many young supporters. After not taking much notice of her condition

Winnie died, fairly young, in the late 1980's after a short but

debilitating final illness. David Clement who visited Major at

this time and took him to see Winnie when she was in hospital

says that her death really upset Major. Major felt, rightly or

wrongly, that the hospital had not done enough for her, and some

of his friends have said that the bereavement soured Major's outlook

on life thereafter.

It is a great shame that since the shop moved to 48, Durban Street, Smethwick, there has been so much social unrest and disturbance in the area. The changes in the economic climate, the socio-cultural mix in the area and in the bicycle using world as well as in Major and Winnie's health that coincided with the move from West Bromwich to Smethwick meant in Major's view Chaos! In his friend, Barry Southall's, strongly held opinion, the move at that time at one swipe effectively wiped Major Nichols Cycles from the face of the known world. And Barry is not the only West Bromwich resident who feels that way. He is indignant that, until that time, cyclists in West Bromwich had been proud that the town was associated with the best bike in the world. Major had regularly received orders from around the world addressed 'Major Nichols, West Bromwich, England', but after the move these contacts and orders mostly ceased. The shop had had callers from US, New Zealand and Germany all beating their way to Reform Street, West Bromwich. Barry considers that if the demolition were to be proposed now, there would be much stronger objections, and a good case could be made for preservation of the shop because of its social history as an example of the excellence that once attached to West Bromwich and Black Country artisan industries.

| Map showing location of Reform Street

shop |

The Smethwick shop was broken into on numerous occasions. Major had been seriously injured in protecting his shop and theft from the premises in the early 1990's resulting in the irreplaceable loss of personal possessions such as valuable watches, and particularly the shop's records of frame numbers and of the owners of custom made machines. Of course by this time the era of cheap imported bicycles had arrived and few people anywhere were buying sports and racing bikes. Major did try building the small wheeled shopping bikes that came in the 1970's after the Moulton small wheeler had briefly shown the way. He tried his new bike round the corner and could not stand the ride, realised he could never build them for the price the High Street shoppers wanted to pay, and gave them up except for repair work.

Strangely, a similar thing happened when 15 years later, and right at the end of his working life, the All Terrain Bike (ATB) latterly called the mountain bike and then even more ubiquitous urban scourge the motocross bikes came up. Ever the technologist, Major made a customer a an ATB frame - but he never came back to collect it - Major's asking price for a hand made frame was probably the reason, and eventually the frame was lost or stolen from the shop. Major never closed the shop however and he kept the increasingly unkempt shop open serving the occasional old customer, repairing wheels, and selling spares. Mostly the customers were local people often children, but as he could not see very well he suffered from the occasional unfriendly older visitor who took advantage of his increasingly poor eyesight and petty pilfering took place.

|

| Major Nichols cycle (photo courtesy

of Josh King) |

In 1998 at age 83 he was attacked one night by youths that he

interrupted in thieving in the shop. During his attempts to repel

them he was hit around the head by a 2 by 4 inch timber so that

a broken skull was suspected. He had tackled them in his pyjamas

and was knocked unconscious but survived though thoroughly battered.

Major was still made of stern stuff and later that year was awarded

the Super Diamond Award in the Birmingham Evening News Awards.

Simon Weston, the Falkland War hero, presented the award to Major.

It was, said Major after wiping away a tear, "one of the

proudest moments of my life".

|

| Nigel Price is another enthusiast

who supplied pictures of his Major Nichols bicycle |

Sadly Major began to withdraw into his own world. Although the shop never closed callers had become less frequent and unless Major could be convinced he knew them callers were mostly sent away empty handed; he had begun not to trust anyone. His old friend Barry Southall continued to visit him on a weekly basis, but Major was clearly sinking. Then in early 2005 he started to become seriously confused. After being found on his own doorstep looking for help, it was obvious that he had became too ill to look after himself and in March 2005 had to be admitted to hospital and was then moved to a nursing home having recovered from heart and respiratory problems. After a short illness he died on 3 August 2005. A number of articles about his life appeared in the local press. His remains were cremated on 31 August 2005 in West Bromwich Crematorium.

|

| Another view of Nigel's Major Nichols |

Many old friends attended the service; at least one arriving on his Major Nichols. An Honour guard of four of his beautiful bikes also stood outside the chapel of rest as his coffin was carried through and a moving address was read out at the service. One of the hymns sung by his old friends had been chosen by the priest as having a refrain appropriate for a master cyclist. This was a Charles Wesley hymn with the refrain "My chains fell off, my heart was free". As it was being sung many of his old friends must have wondered though whether this particular cycling experience, which would of course be a catastrophe due to poor cycle maintenance, could ever have happened to Major. Many must have pondered whether looking up from below, or just perhaps, down from above, Who Knows? Major might well have come out with an expletive such as, when rephrased for this story, "What the heck are they singing about there then?"

The bicycle business

Major had opened his own cycle business on his return from serving in the Navy after the Second World War and slowly built up his bicycle expertise and its reputation for excellence. In fact, his father had run his own bicycle business from the same premises, on the ground floor of the family home. The house at 5 Reform Street, West Bromwich was a corner shop with handsome Georgian bow front shop windows and the living quarters above, now of course long gone. The corner site is now occupied by a parish office.

|

| Picture courtesy of Josh King |

There was once a separate entrance to the cellars of the shop. Friends ruminate with some anguish just how many old frames and bike components might still remain, rusting and forlorn, having been buried down there when bulldozers filled the void left by the cellar with the demolished walls of the house. A half demented Major had effectively closed his mind to the impending demolition and the need to clear his possessions for the move; he was wholly unprepared for the day when the machines finally moved in on his domain. He was largely taken by surprise when the demolition gangs at last appeared. One customer and friend remembers how, at the end, Major's premises stood alone in a sea of rubble as all else was demolished around him. Unlike Canute, Major seemed unable to rationalise events, but was equally unable to stop the tide of events, and Geoff Ault remembers being asked by Major to "Come in and take anything you want; it won't be here tomorrow". Geoff came to the rescue and took several loads of household and shop items away in his Mini.

The shop was the subject of a compulsory purchase order. The road changes never really needed the shop or its land however. Later though, the parish community centre was built where once the shop had stood, much to the Nichols great indignation. Major had been found another property in Smethwick and had received some moving costs, but as usual these were not enough to cover the real costs of moving his home and his shop and business premises, requiring as these latter did, special facilities with precautions for highly combustible solvents and metal heat treatments carried out in close proximity.

Major's father, as well as running his own bicycle shop, may have produced his own cycles under the name Mazzepa. Pat Slater has also told us that he owned shares in the Mazzepa Ballet Company, and it seems likely that this may have been the source of the Mazzepa name. Major has recalled that when young a small bike was built for him to learn to ride on, and it seems possible this was a Mazzepa; he was certainly happy to recount how ownership of such a bike made him the envy of all the other youngsters. Jake Wheatley believes however that Major did not hold the Mazzepa bikes in high esteem and probably never used the name for his own products. However, Major did tell David Clement about his father's involvement with Mazzepa's and David recalls seeing a desk draw with Mazzepa transfers in it in Reform Street, one of which is now in the possession of Jake Wheatley. None of the Mazzepa bicycles appear to have survived, though it is just possible that somewhere in the Black Country one is still waiting to be discovered.

There are no photographs of the Smethwick shop at 48 Durban Road in its prime. It was another corner premises with Major's workshop much further away from the actual shop, and in this new environment Major never felt quite as much at home as in Reform Street. The premises as they were in summer 2005, very much run down and broken into and occupied by a squatter whom the Police seemed unable to evict.

Inevitably this section dealing with the shops ends on a sad note, but perhaps all is not so gloomy. The Curator of the Black Country Living Museum was told about a local master craftsman and had visited the shop in 2003. Major, doubtless thinking "and about bloody time!" had welcomed this recognition and agreed that his workshop fittings should be passed to the Museum when he finally retired so that they could be exhibited there. It is hoped that this will now take place in the near future.

Major Nichols Cycles - The shop and its staff

David Clement and another friend, Tim Harris, recall that Major told them that initially when he returned from the Navy he had known very little about the bicycle business and in particular the skills needed for frame building. Initially therefore the shop was simply a retail business with all the material bought in, presumably much as his father had been doing. Jake Wheatley and David Clement recall that even later on a part of Major's cycle business depended on buying in lower priced mass-produced bicycles from his friend Harold Parsons, who ran Centric Cycles, in Hockley Brook, Hockley. These cheaper end bread and butter bikes included roadsters as well as sports machines. David also recalls that later Major had agency agreements for Viking and Dawes bicycles, and these too sold well from the shop.

|

| Photo courtesy Nigel Price |

As Major told it, he, with considerable help from Harold Parsons,

had taught himself the necessary frame building skills. He created

his own templates from other builder's frames by marking out the

alignment of the frame on his bench. His hand made frames were

always "of a sporting characteristic" and he remembered

that at first he only charged £5.00 for his frames.

One or two people remember that initially the shop had been the

scene of another of Major's enthusiasms, model aircraft. Such

a sharing of shop space between bicycles and other retail areas

was not uncommon after the war when all sorts of items were in

short supply and shop keepers needed to diversify to stay alive.

Terry Nightingale remembers as a young man seeing eye-catching

windows with exciting model aeroplanes, and remembers that at

this time Major was very keen on this hobby.

Recalling this time, Marilyn Smith remembers a typical exchange between her father and Major that went down in family history. "Dad used to call round at Uncle Major's shop, and one day found his him making a remote controlled plane. Dad asked Major if he thought it would actually fly, to which Uncle major replied 'Of course it bloody well will!' summing up Uncle Major's confidence in everything he did. He was a very clever man and did not suffer fools gladly", or doubting Thomas's apparently!

David Clements remembers how, when he was working for Major early in the 1960s, one of his jobs was to drive the firm's van to collect bicycles from Centric Cycles as well as going to Cyclo in Aston for gears sets and spare parts. David in fact was taught to drive by Major, and remembers that Major's old friend Ian Guest of Guest Motors, the West Bromwich Ford agent, supplied the firm's Ford van. This particular van was effectively paid for by a special metal forming and painting contract for Griffin and George, Biological suppliers in which grey wrinkle finish enamel laboratory stands were made; hard work but worth the cash reward was how Major summed it up.

David Clement appears to be the only person, other than Winnie, who worked in the shop with Major. David started helping in the shop as a schoolboy of 14 in 1958, and later at Major's request, became an employee in 1962/3. This situation was forced on Major as he had been uncharacteristically foolish, though typically impulsive, when rekindling a fire at his home and had received severe burns to his face and his hands. He thought the fire was nearly out and used a can of paint thinners on the embers in the hearth; the can caught fire and exploded in his face. Major could not work at first due to his burnt hands and face and needed an experienced assistant, one whom he could trust in the work place; David was the natural choice.

David has many fond memories of working in the shop at Reform Street. Major let him take the van out, delivering bikes to various shops after they have been built, and collecting components from factors such as Anderson's and Cyclo Gears. He recalls how Major would close the shop at lunchtime on Wednesday when he might head off to the Royal Oak in Claverley or call in to see David Wheatley in Anderson's.

David Clement recalls that in the 1950's Major had successfully covertly introduced a system of Kit bikes. This practice, which was widespread though clandestine in the cycle trade, was to avoid the 25% Purchase Tax on complete new bikes. The shop would sell the frame and, quite separately, the rider's choice of components. The salesman would then arrange, by the back door as it were, for the selected components to be collected and assembled by the purchaser (but assembly by the shop could also be arranged if needed). This proved a highly popular commercial arrangement. David remembers Major's trepidation over the inquisitions by the Board of Trade inspectors who would demand access to examine the firm's books of orders to see that these tallied with the number of tube sets that the buying-in books showed.

The bicycles

David Clement notes that when he worked in the shop all the frames carried the frame number on the bottom bracket. The standard marking having the prefix MN followed by, or below which was, a four or five digit production number, consisting of the year as the first two digits then that year's bike production number in annual sequence. Usually the front forks carried only the current year's production number stamped on the steerer tube, this number would be visible only when the forks were removed for the frame. At the time David was with the firm even frames supplied to other firms were given an MN prefix to the number on the bottom bracket. As we now know, Major was not always consistent with this system, some bicycles without the frame number having been found, this was probably a later lapse.

Major always insisted that the chromium plating on his frames was carried out to a very high standard with a good thick copper base. One all chrome frame is recalled; although plating was usually restricted to the front forks and rear stay ends of a frame. In the early 1960's Ablo Plating, whose premises were in Ablo Street, Wolverhampton, carried out the electro-plating. Later it became more difficult to get the same quality and then a variety of companies were used. By the end of the 1980s local industries were disappearing rapidly however, and even Major could no longer get a reliable plater to work on his bicycles. In this period he refused to have a plating finish on his bikes, but this was also general in the cycle trade, plating finishes were now the reserve of specialist restorers of older bikes and were not seen on truly contemporary machines.

|

| Photo courtesy of Nigel Price |

Major had always been very aware of the importance of the appearance of his bikes for advertising his marque. The paint shop was always on the premises as the finish of the bike and its high quality it was an integral part of Major's cycle making. As with everything he did, Major's finishes were exemplary and he was justifiably proud of his work. To see any Major Nichols in its original finish of high gloss colour and superbly styled transfers, is to realise the machine was styled by someone who had that essential flair that turns a well crafted item or design into high art, a beauty to behold. These bikes must have had a comparable impact on their admirers to the awe created by those gorgeous glossy black Sunbeam bicycles with their bright gold lining from that other Black Country town, Wolverhampton, the appearance of which had so impressed cyclists at the turn of the century. Or for that matter the lust induced by the latest sporting Jaguar today. Something beyond expectations, and as a number of my raconteurs remembered, often beyond the pocket of the envious eyes of the then young men.

On a practical level, Tim Harris vividly remembers being told by Major that his paint work was tough, and then being agonised as Major gleefully took a hammer to the paint on one of the shop's stock frames, with shout of "Look, I'll show you how good!" David Clement remembers that the 1960s frames were nearly always brightly coloured finishes often with the transfers on contrasting colour bands. Competition bikes made in the 1960s might well have the Major Nichols logo on both sides of the top tube and the down tube, even the chain stays, and additionally they might have the vertically aligned capitals Major Nichols or just Nichols's down both sides of the seat tube and each arm of the front forks. One such frame can be seen in the photograph of Major in his shop in 1969, a photograph that also shows why some have remembered it as "an Aladdin's cave, with shiny goodies hanging everywhere". In many cases the Major Nichols name was given further prominence by being put in a box of a contrasting colour to the mainframe hue. The 1960s frame owned by Geoff Ault shows this contrast to a nicety.

David Clement recalls one frame in particular, where he went a bit beyond his remit from Major, with some affection. Whilst David was developing his skills in applying flamboyant colours (where a translucent coloured lacquer is applied over a silver or gold base) he had on one frame experimented by fading four flamboyant colours sequentially along the whole of the bike, in the manner of the modern colour fade technique, but carefully balancing the painted areas on all the tubes. David hung the frame up in the shop's window. "What's that thing? Take it down now," squawked Major when he saw it. But David with his young eye for what was wanted prevailed just this once as he was so proud of his work, and it was not long before a customer rushed into the shop and had to have it. As far as Major was concerned it was not what he wanted on his bikes and David never got to make any more fancy multi colour faded frames. David would love to see that frame again, but cannot remember the name of the purchaser, though he thinks it was someone in the Oldbury CC.

Later, in the 1970s and 80s frame finishes became more restrained. Changing fashions led in the 1970s and 80s to the use of more subtle and restrained frame colours and decoration but the transfers always stood out beautifully and complemented the light and lissom lines of the frames. One idiosyncratic feature of Major's enamelling schemes at this time was the unusual but very effective use of colours in picking out the frame lugs. He would highlight the three main lug-lining areas (head, bottom bracket and seat pin clamp) by picking them out in separate colours, commonly such as red, white or blue. Clearly this was best seen on plain backgrounds as on his well known (at this time) frame colour choice of grey for the main tubes. Nevertheless some frames did have the traditional single colour lug lining of silver or gold.

The transfers used by Major were all beautifully made. It appears some were made by HA Peace of Ludgate Hill, Birmingham, but at least latterly they were Kwik-fix special solvent type and made by Eagle Transfers of West Bromwich. There have been several versions of the transfers over the years. The main change in the transfers was the address of the shop.

In the 1970s and 80s the need to identify the more expensive racing frames led to the use of two additional small triangular transfers, both for Record Road Sprint frames, which were intended to be fixed on the front forks. In later years Major ran out of the main head transfers, which would have been used on all his frames. At that time he had largely stopped building frames, and with the small number of frames being made or refinished, was scandalised at the price quoted for a new transfer batch. Typically, he refused the quotation submitted with an angry rebuttal as he considered the price was too high and the order required several hundred sets as a minimum order. He therefore, from that time onwards, had to make head transfers from any transfers still available in the shop. It appears that earlier bikes had a down tube "Major Nichols" transfer in a flowing manuscript font, whilst later bicycles had a bolder name transfer in the more formal "mock Gothic" block capitals, commonly in white with contrasting outline colour. However, it may be that this use of different transfer styles was not just something that changed over the years as in the 1990s, Major told his then new and eager customer, Armajit Singh, that the 'manuscript' transfers had been intended to show that the bicycle carrying them was one of which Major was particularly proud.

Major has been reported by several people as making racing and high quality touring frames for other cycle traders as well as for sale under his own name. For instance, David Clement knows that during 1962/3 the firms listed below ordered frames from Major and then provided him with their own transfers and painting specifications which, he then carried out applied before delivery.

| Wilson Cycles of Aston, Birmingham |

| Southgate Cycles of Gloucester |

| Cliff Peters Cycles of Aston, Birmingham |

| Criterion Cycles in King Street, Dudley |

| A cycle shop in Hall Green, Birmingham, whose name cannot be recalled |

| Bob Mansell Cycles of Hallam Street, West Bromwich. This shop later moved to St Pauls Road, Smethwick on the way to Oldbury |

Tim Harris is certain there could have been many other firms supplied by Major over the years, though of course some of them would just have acted as agents for Major Nichols machines once his reputation for excellence became generally known in the 1960s and 70s. Walter Fowler, in a conversation reported more fully later, was told by Major that he had supplied frames to Bob Jackson Bicycles of Leeds.

At least one other instance of major supplying his bikes to

others is known in some detail. Hill Cycles in Neath was owned

and established by John Williams in 1980. John has now retired

from the shop, but has retained six of his Major Nichols made

bicycles. John became aware of the desirability of Major Nichols

bicycles early on through being a racing cyclist himself, and

altogether he believes he sold between thirty perhaps fifty of

these bicycles. As John tells it he fell in love with Major Nichols

bicycles when he saw them ridden in the weeklong race meetings

in Builth Wells, which attracted racing men from all over Britain.

He contacted Major and immediately his enthusiasm set up a rapport,

which led to Major supplying not only what he wanted in bikes

but also having Hill Cycles transfers made in the same mode as

Major's own transfers by Eagles.

In addition to frames sold by Major to other bicycle shops in

the normal line of business, David Clement recalls that Major

also made special frames for a number of racing teams, possibly

including the Raleigh team, though Bob Mansell believes this contract

might only have been a contract to paint some Raleigh special

products racing frames, as they had a number of very capable frame

builders of their own.

|

| Major Nichols receiving an award

for his bicycles |

Major Nichols frames were always built in the best possible material; tubing from the local specialist suppliers either Accles & Pollack or Reynolds, and most commonly it was Reynolds 531 tubes. Plain gauge tubing, tubes that have a constant thickness, were used for stock frames suitable for sports bicycle buyers. The lighter and more expensive double butted Reynolds 531DB, where the centre part of the three main long tubes has a thinner wall thickness, was used for all custom frames including the racing frames. Later as these lighter more expensive frames could be made from 531 Special (which also became known as 531c tubing) and, later again, just a few used the very special Reynolds 753 tubing which required silver soldering. David Clement recalls that in the early 1960s the stock frames, which only used the relatively expensive 531 tubing for the three main tubes of a frame, had the seat and chain stays made with unclassified Reynolds plain gauge tubing. One easy way to detect these frames was the top of the seat stays, which had the unusual feature of a 'button' shaped top and were gently double tapered like an elongated cigar.

The frame construction technique used by Major was the traditional single frame method. He was asked many times why he did not try to lower costs by using a variety of batch production methods but he always refused, preferring to do each job on the frame himself, and at his own pace. Barry Southall, himself a skilled tool maker, offered to help Major prepare jigs to allow greater rates of production using a batch process, but Major would not hear of it. Major appears never to have allowed any one else to help in the frame making. All his friends conclude Major never at any time anyone else on in the shop to help him even when David Clement worked in the shop, he was never involved in the frame building itself.

All Major Nichols frames differ in some way from each other even if only in the details of the lug design. He had an adjustable template for the mainframe tubes laid out on the workbench. At the start of making a frame for an individual customer Major would have needed to decide a number of key parameters for the new frame. For example, he would take care, interviewing customers in depth so that he could provide what they needed. He would have probably started by asking the inside leg measurement, or perhaps more delicately in the case of a lady, the size of the person for whom the bike was being made and made due allowance for the likely riding style of the individual.

Major apparently never made any ladies bicycles with the traditional ladies dropped top tube frames, he refused on the basis they could never be good frames as in his view this design of frame was not properly rigid. But as a custom bicycle maker, Major would often be approached to make small frames, because the ordinary commercial cycle trade either did not cater for such sizes, or made smaller built adults choose bicycles that had been intended for children and were commonly poorly finished, inadequately 'specced' with accessories and jolly heavy to boot. John Williams of Hill Cycles in Neath remembers having a smaller frame Major Nichols bicycle intended for ladies in his Hill Cycles shop when who should come in but Barry Hoban, then Regional Manager for a components firm, but a man who had been a Tour de France rider and who obviously knew a good bike when he saw one. "What a little beauty" was his reaction when he saw the Major Nichols machine.

We can never now know how many frame Major made in his life, as his shop records were stolen from the Durban Road shop. Additionally, due to the fact that the Major Nichols frame numbering system only referred to the number built in any one year and did not show the total made as the years rolled on, as well as the fact that he built many frame sets for other concerns, it is now impractical to gauge just how many frames he made in his working life which spanned almost 50 years. Although he was asked many times Major himself was never prepared to venture how many he had made. Indeed latterly when it was put to him that his frame numbering would give at least a minimum estimate if he could recall the average number made in a year, he would lose patience and say that he had attached little significance to the frame number when working for a customer, just using whatever took his fancy.

Anecdotes suggest that despite the fact that currently only about 60 bikes are known to survive, there would have been very many more built. For example, Paul Arnold, who knew Major and who raced at Halesowen track in the 1970s, remembers that at that time Major Nichols bikes were the dominant racing machine and apart from being the most favoured machine on the track, a good many of the spectators would also have been riding one, and indeed they had been the machine of choice in local clubs in the Black Country; providing you could afford a top notch bicycle since the middle 1950s.

Major would make you a bicycle for touring, general use, or racing but as far as is known he never gave a special model name to any one style, strangely the shop never issued a catalogue or advertised even in the local press. In terms of quality however Major did distinguish his better, mostly custom frames, in two ways. As described earlier he has said that bikes he thought worthy of his name had a manuscript Major Nichols transfer on the top tube. Then later, frames using the lighter versions of double butted Reynolds 531 or possibly the later Reynolds 753 tubing, built mostly in the 1970s, had two small 'Record Road Sprint'' transfers on the tops of the front forks. Roger Allen remembers he and his club-mates in West Bromwich CTC always referred to their lightweight Major Nichols as "Records".

Many of the now classic Major Nichols frames of the 1970s and 1980s use a style for the anchorage of the tops of the seat stays in which the stays appear to be brought over the top of the frame, as shown in the photograph below. This style is known as a wrap-over stay. Barry Southall believes that Major's original wrap-over design, which was probably in use prior to the late 1960s, used a round bar or tube over the top tube. After that period, the round bar/tube became a more elegant and thin strap wrap-over. Barry thinks this change was because the thin strap wrap-over had been a WH Gameson design feature and it was only when Gameson stopped building, circa 1968, that Major felt able to copy this elegant detail.

Concluding remarks

Major in his prime, which was perhaps from the late 1960s in Reform Street to his first decade in Durban Road when Winnie was still alive and well, had built up a reputation for superb sporting bicycles that was second to none in the West Midlands. Indeed, his fame spread well beyond the local area as evidenced by the enthusiastic support in South Wales, and the overseas interest in his products. He was generous in helping sporting cyclists and certainly Jake Wheatley was not the only racing man to benefit from his support for likely lads. His friends recall the days when a Major Nichols was a by-word for excellence, and in the less prosaic language and speech of Wales, where enthusiasm still runs high, Major has been described as the Michelangelo of frame making.

Nearly all the bicycles that Major built were lightweight bikes and many owners revered their machines, recognising how special they were, and that they were the product of a very talented frame builder. Armajit Singh becomes panegyric with delight over being on a Major Nichols, whilst Barry Southall becomes eulogistic on the subject and swears that a Major Nichols could always outrun any other bike downhill; in his understated view they were just magic, and the handling superb.

Major never doubted that customers were right to come to his doors, but they needed to be patient, perhaps quiet and preferably reverential. If they talked back at him, or if he did not take to them, he was well known to be likely to say "Oh, clear off then" and leave them to their own devices. Major's bikes and his customers loyalty to him show that he undoubtedly had a superlative and natural feel for bicycle frame design and subsequent development, skills similar in kind to those shown by another self taught and ultimately tortured engineer, Colin Chapman of Lotus Cars. In both cases their productions remain behind them, highly prized among those who were lucky to be around when they were made and now being passed on to a younger generation who are equally appreciative of fine craftsmanship.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the following key collaborators for all their help and patience in preparing this story. In alphabetic order, the team members were: David Clement, customer and one time employee; Tim Harris, friend and one time owner of Criterion Cycles, Dudley; Barry Southall, old friend and customer; and John (aka Jake) Wheatley, old friend, once upon a time Major's Best man and a highly successful track rider who received supported by Major Nichols Cycles. A list of all the people who have contributed to this history is provided below, if I have omitted any one's name to whom I have spoken, I apologise, any oversight is not intentional. Equally should any reader have any further information on Major Nichols, whether on the man, his family or his bicycles I should be delighted to hear from them.

Roger Allen, Kingswinford,

Paul Arnold, Stourbridge;

Geoff Ault, Leominster;

David Clement, Wigmore,

Stuart Edinborough, Hereford,

Eddie French, Cardiff,

Tim Harris, Stourbridge;

Paul Kimberley, Malvern;

Bob Mansell, Oldbury;

TA Nightingale, Cornwall:

Doug Pinkerton, Rednal;

Alan Powys, Swansea;

Doug Read, Smethwick;

Armajit Singh, Halesowen;

Pat & Philip Slater, Smethwick;

Mrs M Smith, Over Whitacre,

Barry Southwall, West Bromwich,

Jake Wheatley, Worcester;

Keith Wilkes, Smethwick;

John Williams, Neath.

Some Memories Meeting 5 May 2007

The second ride for Major Nichols enthusiasts enjoyed the last really good day of the spring 2007 drought period, so well done! I know I thoroughly enjoyed the day and a number of you have written to say you did as well so we will certainly be trying to pick another good one in 2008.

We met at the Swan in Chaddesley Corbet apparently on the first day of opening for the new owners, so thanks for being patient with the somewhat slow service we received at the bar. The staff appeared willing but woefully lacked impetus, despite smiling through it all. Tim Harris and I will review this location and others which have some historic connection with Major for next Year.

We had a short period of general chat in the garden before starting the reminiscing in the main bar, and apologies to those of you for whom the shape of the bar area made it difficult to hear what some of the speakers were saying. We had contributions from Jake Wheatley, who was one of Major’s first supported riders and who was later his Best Man, Frank Nichols who recalled his own visits to his granfather’s house in Reform Street in the days before the family split soured relations for the rest of Major’s adult life, Saeed Ghinai and Felix Ormerod who knew Major in the 1980’s and finally we were so pleased to welcome Rob Newton who was just cycling through the village on his Major Nichols and was hauled in to tell us about the four Major Nichols bicycles in his life -Welcome to the group, Rob!

|

Nick Adams | Felix Ormerod | Josh King

| Al Smith | Frank Nichols | John Whitehouse | Saeed Ghinai

| Walter Fowler | Paul Arnold | Paul Kimberley | Rob Newton Jr | Nigel Price | Robin Walker | Graham Nevett |

After lunch we dispersed on the long and short rides planned by

Route meister Tim Harris, the long ride very ably lead by Walter

Fowler. Thanks to both of you for that assistance and I know the

rides were greatly enjoyed by the riders.

I am showing overleaf one group photo sent in by Barbara Adams and I already have some more taken on your behalf during the day by David Clement. I would be grateful for a copy of any other photos you may have taken during the day, and will be happy to send the whole collection of these photos on a CD to anyone who wants a copy and who sends me £1in stamps to cover my costs and postage - a copy will also be sent to the BLACKCOUNTRYMAN magazine.

Two final things- on leaving the Swan on the day I took with me a red or plum coloured long sleeved fleece or sweat shirt made by St Michaels- size large. I assume it was one of ours but no one has claimed it -or asked the Swan staff for it -but if it is yours you just need to ask me for it back! The last is that some of you know that ‘Marque Enthusiast’ is a voluntary role that I hold within the Veteran-Cycle Club, which runs many rides similar to this meeting -just ask me if you would like to join the V-CC which at £20 pa is startling good value for the friends you will make and the beautifully produced bicycle magazines you will receive.

Best wishes,

Alvin

Castle Cottage,

Wigmore,

Leominster

HR6 9UA Herefordshire