The Nine-Locks Ordeal - 1869

by Mick Pearson

In March 1869 the Earl of Dudley's Ninelocks pit at Brierley Hill was the scene of a week-long drama as a dozen or so miners became entombed in their pit.

George Skidmore was one of those miners and told his account in 1896 when he was then the licensee of a public house in Stafford Street, Dudley.

On the night the ordeal started (Tuesday) thirteen miners went down into the pit to work as usual. Their problems started at the end of the shift when they couldn't get up the shaft for water and had to retreat to the safest place they could find.

Skidmore said that he slept for most of the time he was trapped underground. He gave his food to two of the younger miners (young Tommy Timmins and Joe Pearson). As time wore on (the miners were trapped for nigh on a week) the group huddled together for warmth. Some got so hungry they ate the candles they had with them, leaving them all in darkness. Following this some even ate the leather from their straps and shoes, and pieces of coal.

While the miners were waiting and surviving (only one of the 13 perished) the rescue effort was going on above them. Being a mine owned by the Earl of Dudley the equipment was good for the day. A pump in operation at the pit took 250 gallons with each stroke and a tank that drew 2 1/2 tons of water, every time. The actions of the tank, moving and removing the water, meant that fresh air kept circulating.

Eventually the miners were taken out on a raft, all were pleased to see daylight I am sure.

The Names

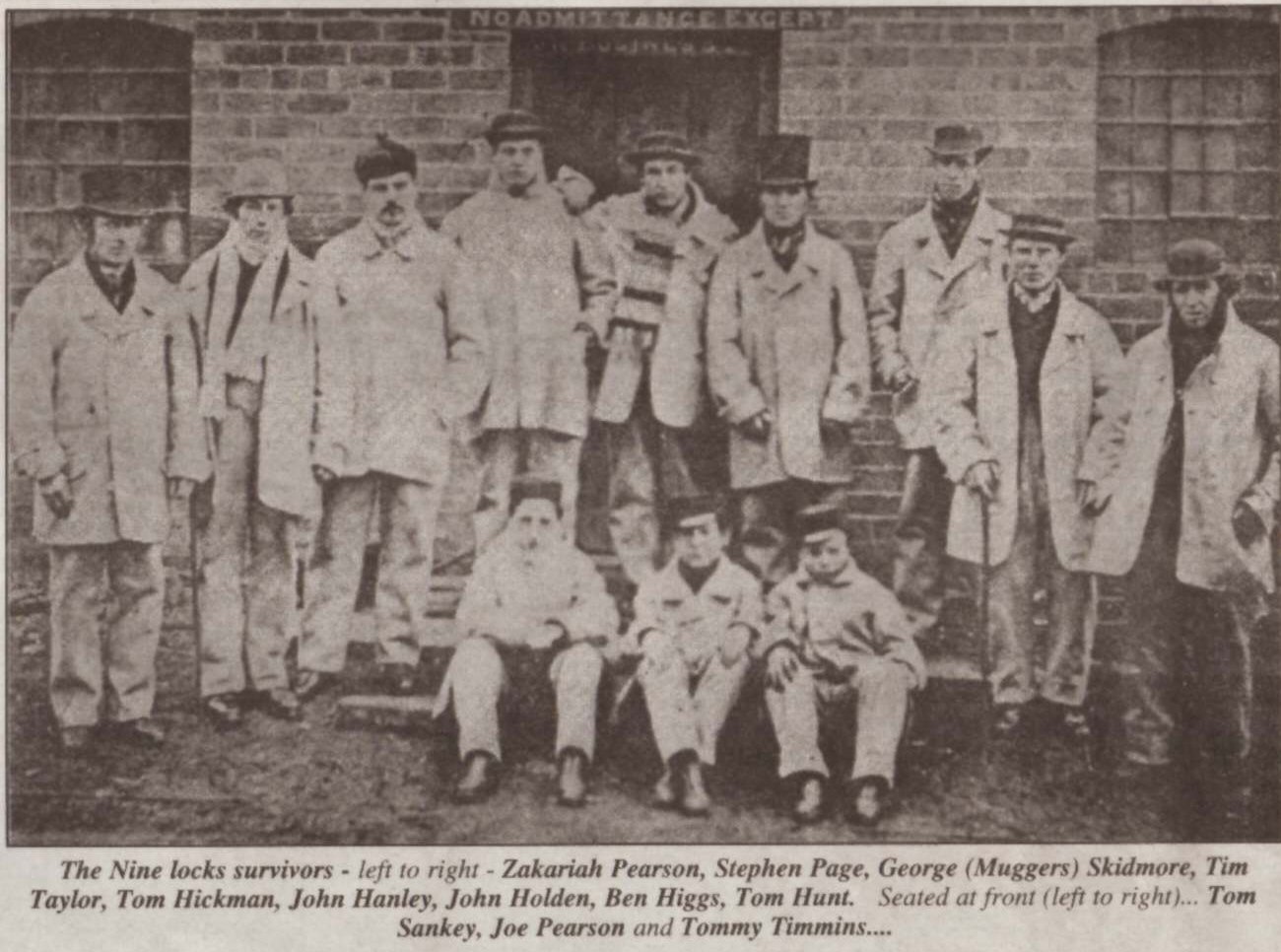

Tom Hunt, Ben Higgs, Jack Holden, Johnnie Handley, Tim Taylor, David Hickman, Steve Page, George (Muggers) Skidmore, Zach Pearson, and three lads Tommy Timmins, Tom Sankey and Joe Pearson.

The miner who died, William Ashman, appeared to have been affected mentally by the situation and wandered off alone, he died of "the damp".

Joseph Pearson went on to become a minister of the Gospel.

A search of the 1851 census (from the same Black Country Bugle article found a number of those involved in the incident:

Zachariah Pearson was born in 1816 at Kingswinford. He married Mary Ann (who was 33 in 1851) and lived at Brierley Hill. In 1851 three children are recorded as part of the Pearson family - Sarah (11), Deliah (6) and Bathsheba (3).

Tim Taylor - lived with his parents John (34) and Manaria (30) who in 1851 had four children - Caroline (10), Timothy (7), Ann Maria (5) and Phoebe (7 mths) all were born in Brockmoor.

Stephen Page - in 1851 lived with his mother Eliza (47) a widow, there were four children - Catherine (19), Zephania (10), Stephen (7) and Benjamin (5).

Tom Hickman - in 1851 was living with his parents George (33 in 1851) from Ireland and Hannah (30). In 1851 their children were Ellen (10), Mary Ann (8), Thomas (5), Sarah (3), George (1). They lived in Level Street, Brierley Hill.

John Holden's family circumstances in 1851 were that he lived with his parents John (41) born in Worcester and Ann (38). The children were Thomas (18), Charlotte (13), John (10), Sarah (8), Noah (4) and Richard (1), they lived on Dudley Road Brierley Hill.

George Skidmore - update to info on George - in 1851 was living with parents Obadiah (43) and Emma (40). There were 10 children living with their parents - Diannah (19), Sebrina (17), George (10) (already a miner in 1851), Mary (12), Jane (10), Noah and David (8), Ann (6), Harriet (3) and Sarah (4 months).

(It appears from the research carried out by Linda Moffatt into her Skidmore family that the information above is incorrect. Linda has given me permission to re-produce the correct information and I have done so below. Linda has produced a book - "Skidmore Families of the Black Country and Birmingham 1600-1900". Please read the review by Peter Skidmore, which also gives details as to how you can obtain the book. Judging by the depth of research I have read Linda will be providing a wealth of information relating to the Skidmore family. If you wish me to pass on any messages to Linda about the Skidmores or her research please email me) - For details of the book, click here => review

Benjamin Higgs was 24 in 1851, he was already a miner married to Ann (23). Their children were William (4) and Mary (2). They lived at Rocks Hill between Brettell Lane and The Delph.

The three youngest members of the group were not born in 1851.

Other Local Mining Accidents

Life appears cheap in the mid-19th century and mining accidents were very common. In November 1872 22 miners lost their lives at Pelsall Colliery. Smaller disasters involving single death or serious injury were much more common.

The Brierley Hill Advertiser of Saturday 23rd May 1857 reports "The death of a 16 year old and suffocation of John M'clue". The 16 year old was William Burns who fell to his death at 5pm on the 21st of May at Lower Pit, Kingswinford. He had been placing timber in the skips to send down to the pit, and got pulled down when his hand became entangled in the chain.

On the same day another accident claimed the life of John M'clue at Number 1 Pit at Moor Lane in Brierley Hill.

The following day William Beddows lost his life at Mr King's Pits at Netherend following a fall.

More tragedy at around the same time at Cooper's Bank in Dudley. One man lost his life and another had a miraculous escape. Number 7, Cooper's Bank Colliery, about a mile from Dudley on the road to Himley. Benjamin Evans and Uriah Fellows were tasked to go to an area of the mine about 100 yards from the bottom. The men worked, Fellows with a pick and Evans raking away the slack. At about 11.30am a crash was heard and a bump of coal or earth. An estimate would be about 10 tons of material fell on the men.

Fellows legs were trapped by the debris and raised the alarm. Other workers raced to his aid and succeeded in freeing him from his position. A few seconds later a further bump of earth, upwards of 50 tons, came down, exactly where Fellows had been trapped. Of Evans no signs could be seen or heard, it was assumed he must have been killed. The search for Evans body would be a formidable one.

Men worked carefully throughout the day and night of the incident, and into Tuesday until 2pm when they reached the body. Despite earth still falling and conditions of "damp" the remains of Evans were soon brought out. He left a widow and 3 young children to mourn his premature death. At the subsequent inquest a verdict of "accidental death" was returned.

Mining in the Black Country

The Black Country's undisputed "Lord of Iron" was the Earl of Dudley.

From ancient times it was known that Staffordshire was rich in ironstone and coal. During the Roman occupation iron was manufactured in the Dudley area by primitive means. During the 19th century the Earl of Dudley was to own the ground under which lay the seam of coal 10-15 yards thick that would provide the fuel for the ironmaking and the industry that would make the Black Country.

Iron made by the Earl would be used to make the chains, cables, anchors, grates, fenders, fireirons and nails. Samuel Griffiths wrote in "Griffiths Guide to the Iron Trade of Great Britain" (published 1873) "Although the atmosphere becomes purer as we get to the higher ground of Brierley Hill (Lord Dudley's famous Round Oak works are here) nevertheless here also, as far as the eye can reach, on all sides, tall chimneys vomit forth clouds of smoke, and the sulphurous flames of the fiery furnaces are observed in all directions."

This description is not unusual for this period in the Black Country's history. The author goes on to extoll the virtues of the Round Oak complex, the perfection of the arrangements for loading and unloading of coal, iron and all other materials. He enthused about the efficiency, which secured minimum labour costs for the manual power exerted.

Baggeridge Colliery

Nine Locks was owned by the Earl of Dudley, another of his pits was that at Baggeridge. It was a late addition to the Black Country coalfield. It would be a 'showpiece coalpit' designed to project the Earl's family image as humane and caring employees.

Boys started working at the pit on leaving school at 14, starting work meant that the boys could have their first pair of long trousers, something they were very proud of.

Coal was fetched and delivered in horse drawn carts. On the way from the mine coal would fall from the carts, village children would scramble to pick up the fallen pieces of coal. A further bonus was the ready supply of fresh manure - ideal for the roses and rhubarb.

Miners wore clogs with replaceable studs (called sprigs). The clatter of the clogs could be heard as they went to and from work. Later on the clogs were replaced with steel toecapped boots. Transport to and from work in the early days was shanks pony or bicycle, later they were taken to and from work by coach.

George Skidmore Updated Information

GEORGE SKIDMORE, son of James and Margaret (Eardley) Skidmore, was born on 3 April 1847 and baptised on 25 April at Brierley Hill.

George Skidmore was a survivor of the famous Nine Locks pit disaster which took place at No.29 Pit of the Earl of Dudley's Wallows Colliery in Locks Lane, Brierley Hill in March 1869. He recalled the events in 1896 when in conversation with other miners in the Duke of Sussex public house in Stafford Street, Dudley, where he was landlord. This was recorded by Thomas Siviter in his family Bible and relayed to a local magazine[1] by Mr Siviter's son nearly one hundred years later. The following account of events also includes material collated by Mrs Sue Brown of Sunderland, great granddaughter of George Skidmore's brother Thomas. Mrs Brown has spoken with Mr Alec Garrett whose father worked in mines all his life and for several years travelled with 'Muggers' Skidmore. The fact that 'Muggers' was George Skidmore was confirmed by a Mrs Millward of Stourbridge, granddaughter of George's brother Benjamin Skidmore [283].

On Tuesday 16 March 1869 ten men, three boys aged 14 and six ponies went down Nine Locks pit to cut coal overnight. George Skidmore, aged 21 and single, was amongst them. Once underground the men and boys separated into two teams to carry out their work in different tunnels. When they started to go up after the shift the shaft was blocked with water. George found himself with four other men and two lads. They found the safest place they could and soon fell asleep. George said he had been drinking and did not need his supper of pork and bread and when the young lads of the shift began to cry with hunger, along with the other men he gave them his meal. For water they drank the flood water using their metal flasks and taking the precaution of covering the mouthpiece with cloth in an effort to purify it. Timothy Taylor, aged 24, is reported to have regularly swum to the shaft to report back on the rescue attempts, and on one occasion narrowly missed being hit by the drugon.

Above ground, the flood was first discovered around 3.00 am in the morning of March 17 and the pumps were set to work. The engine house pump was capable of pumping out 540 gallons per minute. In addition a drugon was geared to the upper shaft and emptied at the rate of 30 hundredweight per hour. Pumps were brought in from other pits and the combined efforts removed 250 tons of water per hour - yet in the first 24 hours the level of water in the shaft had only fallen by 16 inches. Around 1.00 am on the following Sunday morning, part of the machinery broke free and a section of the pumps had to be closed down to repair it. During the ensuing quiet the trapped men's voices were heard, but it took a further nine hours of pumping, and battling against the 'black damp' which followed the dropping level of water, before the first men could be brought out. Thomas Brown sailed a raft into the tunnel from the shaft, collecting the men one at a time and swimming alongside the raft to get them out. By 4.00 pm on Monday George was brought out, still strong enough to walk unaided and declaring he could walk home and needed no medical attention. A cab was provided for him, while the others remained under medical supervision.

A message from Linda about the information:

I know of 3 George Skidmores born or living in Brierley Hill in 1869.

If we are to believe the accounts of the time George Skidmore the survivor was 21, so born 1847/48.

I think you will find that Obadiah and Emma's son was 15 in 1851, not 10. So born 1835/36. His baptism at Oldswinford was in February 1836. Would have been 34 or 35 at the time of the Nine Locks disaster.

The next George to eliminate is the one born in B.Hill in 1843. Like the Nine Locks George he travelled around the country, mining in Derbyshire and Yorkshire. He was born in mid-1853, son of John and Amelia (Askins) Skidmore. He married Ann Geary and was with his family in Northumberland by time of 1901 census.

Which leaves George son of James and Margaret (Eardley) Skidmore. Born April 1847 so was nearly 22 at time of the disaster in march 1869. I have found him in 1871 census aged 23 and 1881 census aged 33. Have found him in 1901 though his and wife's ages wrong. He was a beerhouse keeper in Dudley which tallies with Mr Siviter's recollections. Have only seen the index, not the actual census page.

Further information from Linda:

Taken from The Brierley Hill Advertiser 6 Oct 1888.

'On Thursday an elderly man named James Skidmore of John Street, employed as a wagon oiler on Lord Dudley's estate at Round Oak, got between the buffers of 2 trains, and was badly crushed about the body. He was removed to the Guest Hospital, and there succumbed to his injuries. The deceased was a well known character. He was an old miner and has had narrow escapes from death on more than one occasion. As the father of the man 'Mughouse' [George] who was one of those stopped in the Nine Locks pit years ago, the deceased will be remembered by many in the locality'.

From June Tonks, I have received the following:

My daughter e-mailed me the article about the nine locks pit disaster. My father was John Handley, not the one in the article of course, that was his great, perhaps great-great grandfather, how you wish you had listened more when you had the chance. My father John Handley was born in the Chapel street area of Brierley Hill in 1914, and lived in Brierley Hill most of his life until a few years before his death in November 2002.I grew up knowing the story, and have often wanted to write to the Bugle which has carried the story a few times, but have always spelt the name Hanley instead of Handley. My fathers brother still lives in Brierley Hill, in the same house they moved to when the Chapel steet slum clearance was carried out. If I can be of any help in any future research, please e-mail me.

(Added 20 May 2015) Andrea Edwards is a descendant of John Handley from the Kingswinford area (great great grandfather). Her great grandfather was one of his sons and believes that he was the brother of the John Handley mentioned and photographed in the article. If June Tonks reads this could she contact the Society via any of the email addresses on this site. Mike

From Gill Cash I have received the following:

My name is Gill Cash, I have been researching my family tree for almost 15 years and the information on the above disaster was given to me by my aunt, who still lives in Brierley Hill. I have sent all this information to another website and also have details on my own website.

My great, great grandfather was Tom Hunt, dob 1831 and one of the survivors of this disaster. I notice that his name seems to be missing off the list of names, but I do have further information if you are interested.

Thomas Hunt was born as I said in 1831 and from what I have colated he was born in Belbroughton, Bromsgrove. He married Ednah Truman dob 1835, and married in St Thomas's church, Dudley in 1854. At the time of his incarceration he had the following children,

Mary Maria Hunt, Thomas Hunt junior, William Henry, Eliza and Sarah. Thomas died some time after 1891 but no exact year found. His wife Ednah died in 1889 of cancer. In 1861 Thomas and Ednah were living at 71 Fenton Street, Brierley Hill and later moved to Parkes Street.

Regards Gill Cash

(As always, anyone wishing to comment on this piece of the jigsaw please email me and I will pass on your email to the originator - editor)

Credits

- "Old Family Bible provides eye-witness account of 1869 'Ninelocks' ordeal!" (detail for article provided by a family bible lent by Frank Siviter. His father Thomas interviewed George Skidmore in 1896) - Black Country Bugle Annual 1989

- Black Country Bugle 18/11/1999 (census details and photograph), 24/5/01 re mining disasters, 9/8/01 re mining in the Black Country, June 1998 re Baggeridge

- Linda Moffatt - currently researching book - working title "Skidmore Families of the West Midlands 1600-1900" - soon to be published. Please email me for contact details

BOOK REVIEW

Skidmore Families of the Black Country and Birmingham, 1600-1900

Linda Moffatt's long awaited book Skidmore Families of the Black Country and Birmingham,1600-1900 is now published. It is the product of 20 years of dedicated meticulous research and, as a result, anyone who has an interest in the Skidmore families, who have their origins in the Black Country and Birmingham, is offered a veritable encyclopaedia of information concerning these families. This definitive study is more than simply a catalogue of families and their component generations.

The Skidmores of the Black Country are analysed first, because the family was numerically much stronger in this area than in nearby Birmingham. In a detailed introduction Linda puts the Black Country family into context by defining and describing the parishes of Kingswinford and Oldswinford to which the overwhelming majority of Black Country Skidmore can trace their origin. This informative and comprehensive introduction should enable anyone who is not familiar with this area to find their 'bearings'. It contains three maps, plus information concerning other maps which may prove useful, a detailed list of surrounding parishes, a pronunciation guide to local place names and a list of local Registry offices, showing the areas that they serve. Additionally there is a guide to 'how to read' the text. A sample page has been annotated to show not only the significance of certain pieces of information, but also how this information can be linked to entries elsewhere in the book.

Following this introduction the first chapter deals appropriately with the first generation of Skidmores in Kingswinford, namely the children of William Skidmore and Joyce Bache (or Batch) who were married in the parish church, St Mary's, in 1625. Thereafter a chapter is devoted to each successive generation -nine in total- to trace the evolution of the family up to 1900. In doing so it becomes clear that by the end of the nineteenth century Skidmores were to be found not only throughout the Black Country, but also in the coal and iron making areas of Lancashire and Yorkshire to which they had migrated in search of work, as well as in North America and Australasia.

In dealing with the Birmingham based Skidmore and Scudamore families - and their descendants in Coventry and London - Linda adopts a similar approach, albeit on a smaller scale, to that used to analyse the Black Country families and, accordingly, begins by putting the study in context by describing the nature of industry and employment in the city, as well as listing the parishes in which most marriages and baptisms occurred.

This mass of information which is contained in 349 pages is underpinned by no fewer than 78 pages of family trees which enable the reader to see the relationship between the various branches and more importantly to trace their own particular line of descent.

This truly encyclopaedic work is rounded off by numerous appendices covering topics which have not been fully explained in the text, a detailed bibliography and a comprehensive index.

This book is a must for anyone interested in researching their Black Country or Birmingham Skidmore origins. Given the current price of books in high street shops, this is a bargain at £30 (including postage and packing) for U.K. residents and the same for surface mail to North America and Australasia (£40 by air mail).

Peter Skidmore, historian and local history author, Wollaston, Stourbridge 2004

Payment should be sent to the author, cheques payable to Linda Moffatt. Overseas buyers should send sterling cheques or use Paypal or Western Union.

Mrs Linda Moffatt

Yellow Lodge, Barton Stacey, WINCHESTER, SO21 3RS, England