Covering an area of several acres between Brierley

Hill and Old Hill, and bounded on the west by Netherton, and the

east by Cradley Heath, was Saltwells Colliery.

- The brooch coal

- The twofeet coal

- The thick coal

- The heathen coal

Beneath the Heathen coal was the white ironstone, a seam about

4 feet thick containing several layers of ironstone. There was

a ready market for ironstone, it was used as a flux in smelting

other ironstone or iron ores.

In total 33 mines made up the colliery, each with their own

winding plant and means of ventilation. The winding plants were

horizontal steam engines of 18hp geared to the drum of about

8 feet in diameter. At the number 27 pit (at Darby End in Netherton)

the winding plant was known as "Iron Jack" - a vertical

steam cylinder connected to a beam at one end and the other

end of the beam connected to the winding drum.

The number 20 pit had the central pumping station with a large

steam vertical cylinder having a very heavy flywheel lubricated

by a water jet.

|

|

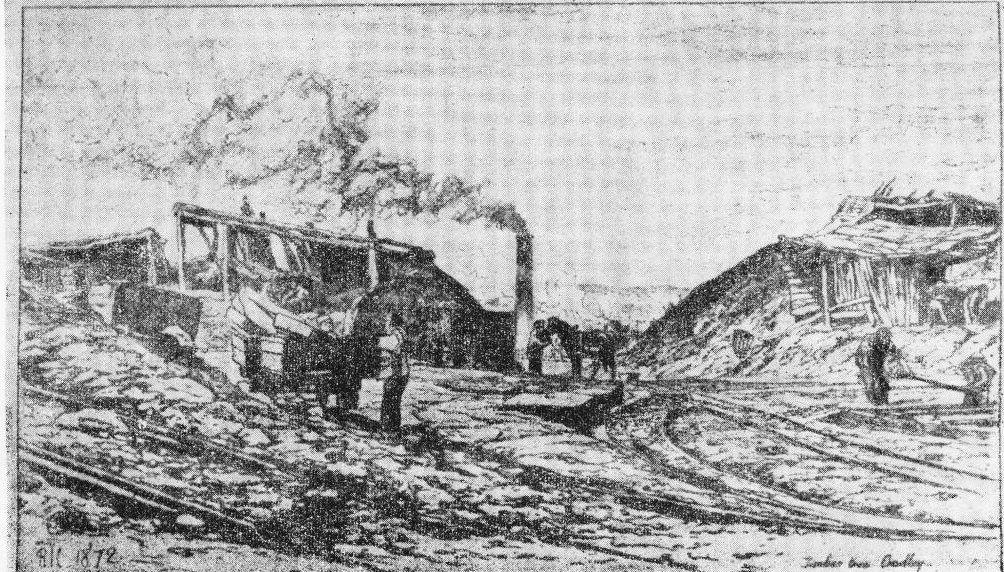

Timber

Tree Colliery Cradley (from etching by RS Chattock 1872

|

The actual mining of the coal and ironstone was undertaken

by "Charter masters", specially qualified men with

training and experience, often being the sons of charter masters.

These were contracted with the Earl's mining agents to supply

the labour, horses, tools, candles, explosives and light beer

to be sent down in small kegs at midday. They were not responsible

for the winding plants and the sinking of shafts. They were

paid tonnage rates, the rates were obtained by weighing machines

on the private railway and by the guaging of canal boats.

The miners were paid on Saturday, the Saturday working day

being the same as other days meant that the wives could not

do their shopping until late in the day, sometimes as late as

midnight. This was later changed to Friday. If the free pit

beer was not up to standard the men would complain and frequently

refuse to work. To remove this problem it was agreed with the

miners' agents to pay an increase on wage rates.

The Government Mining Inspectors recommended that the Charter

Masters be relieved of supplying the timber used for support

of roadways and working places in order to remove any tendency

to economise and thereby increase the likelihood of falls. This

was implemented by the Charter Masters purchasing supplies and

the accounts were passed to the Earl's agents for payment, charter

rates being adjusted to cover the change in conditions. This

change had no effect on accident rates.

The last pair of shafts to be sunk was the number 33 pit situated

at Quarry Bank. The coal measures were lying at an angle of

45 degrees to the horizontal so that a great thickness was found

in the shafts. This was further complicated by the fact that

if a roadway had to be driven in the same section of the seam,

it was continually altering direction and describing a curved

formation on the plan.

A large area of the coal to be worked lay under what was known

as the Cradley Pool, which was used for pleasure with rowing

boats. The effect of subsidence of the surface is naturally

greater with a thick seam than a thin one, so that the pool

was drained off into the Mouse Sweet brook (at the eastern edge

of the colliery) and into the River Stour to prevent any liability

of flooding at the workings. Another large area lay under the

surface closely covered by buildings, houses, shops and small

factories. The Earl had the legal right to mine coal without

being liable to damages. In fact he created a fund for paying

compensation to people suffering loss. With their shares of

the compensation two owners of factories purchased land elsewhere

where they would be free of subsidence and had room for extensions.

Surveying of workings under these conditions presented difficulties

and in order to reduce the interference by men and horses at

work, when Mr Poole became surveyor of the mine, arrangements

were made that the surveying was done after the day shifts work.

The surface winding plant was modern in design, a pair of horizontal

steam engines directly coupled to the drums. These engines could

accelerate the motion of the cage faster than the pithead pulley

would respond, the slipping of the winding rope on the pulley

accounted for excessive wear of both rope and pulley. It is

said that a race had been run between a stone being dropped

with the coomencement of the descent of the cage. Mr Poole never

asked to be let down slowly but always took the precaution of

filling his lungs to full capacity at the start.

Number 33 pit was the only pit to have a steam-driven ventilating

fan. The ventilating current at the other pits was produced

by a fire in a recess in the side of the shaft near the bottom

of the pit. It was the duty of the cager or onsetter to attend

to this fire. Another method was to install a steam pipe from

the boilers down the shaft and near the bottom of the pit connected

with a circular pipe perforated with holes to direct the steam

in upward jets.

A duty of Mr Poole as an apprentice was to pay a monthly visit

to each mine to test the flow of air passing through with an

anemometer. A register of the results of these visits was kept

in the mining office and the manager could order an investigation

if there appeared to be less than the average quantity flowing.

To get a correct quantity of air, it was necessary to have someone

to time a minute's run and the anemometer to be slowly moved

from side to side and from roof to floor.